I love science fiction.

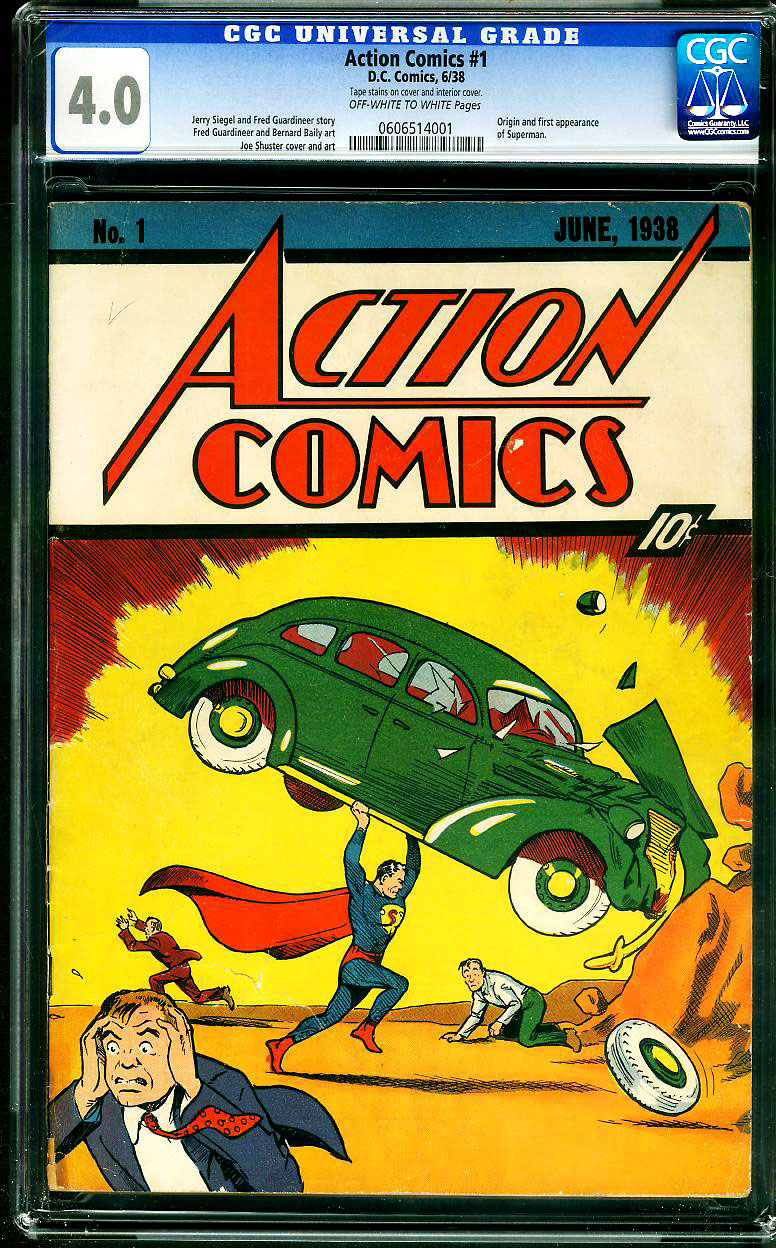

I love science fiction.I am a voracious reader of nearly everything but it was not always so. I began my reading career with comic books. My uncles, some of whom are only a few years older than me, had a large collection of comics that they had outgrown by the time I began reading, and so they didn’t care as much about them as I did, and I cared about them a lot. A whole lot.

My mom would get after me about reading comics, but I kept up reading them, kept up for longer than many people do – I bought my last comic when I was about 23, and I still sometimes miss them. My mom thought it was no good to read comics because she didn’t see them as anything worth reading; they were in her opinion junk that would hold me back from greater pursuits. (She thought the same thing about law school, I believe.)

She initially would have feared she was right, even though time proved her wrong. As I said, I read nearly everything now. My bookshelves contain books like Gladwell’s Blink and the complete Calvin & Hobbes collection, the Grisham thrillers people buy me, the complete works of John Irving, and more, all co-existing with the six Harry Potter books that I’ve bought for myself. I share them with the kids, but they were bought for me and mostly by me. (I’m eagerly awaiting number seven, which was pre-ordered for me as a Father’s Day gift.)

That shows that time proved Mom wrong, but she didn’t know that then and would not have known that early on because from comics I graduated onto science fiction and fantasy, with an emphasis on science fiction that was driven simultaneously by my love for reading and the growth in science fiction that briefly accompanied the release of Star Wars, which when it was released was simply called “Star Wars,” so far as I can recall, and was, so far as I can tell, intended simply to be a standalone movie.

I can tell it was intended as a stand-alone movie, and I know that George Lucas is full of bunk when he talks about how it was always part four of a six-installment serial. That kind of talk has been going on for as long as I can recall. I remember after The Empire Strikes Back came out, the neighbor kid (the same one who told me about Lime Jell-O) telling me that Star Wars was actually supposed to be a 10-part (ten!) series and that the next movies would go back to the story before Star Wars and the only characters from the first two movies we had seen would be R2D2 and C-3PO. And I laughed and said no way, who would ever watch a movie that didn’t have Luke Skywalker and Han Solo in it? As it turns out, I was wrong and the neighbor kid was mostly right. I don’t know where he got his information from. He probably grew up to be a Spanish Teacher or some guy from work. I, at least, watched movies that didn’t have Luke and Han and enjoyed them – yes, even the Phantom Menace, since Jar-Jar was nowhere near as annoying as Ewoks.

That all goes to show you that even back in the glory days of the 80s, the legend was that Star Wars itself - -the movie people now think of as “A New Hope,”—was part of a bigger story. But like I said, I’m here to tell you that’s claptrap. Star Wars was intended as a standalone movie that Lucas hoped would lead to a sequel, maybe (although, if you think back to when Star Wars came out, the movie business had not yet warped into what it is today, all sequels and remakes) but one which Lucas had designed to tell the beginning, middle, and end of one single story.

How do I know this? Not because I’m privy to George Lucas’ mind, or any other insider knowledge. I know it because of this: There’s NO WAY, if you’re going to make ten, or six, or even three, movies, that you put the Death Star in the 4th episode. NO WAY. It’s simply not going to be done. The Death Star is the big payoff, the ultimate weapon, the final monster to beat before advancing. You can’t top the Death Star as a weapon, as a foe, as a destroyer of planets. So unless you want your high point to come 2/3 of the way through your story, you do not intentionally put the Death Star at episode four.

Look at other movies and books. When did the Fellowship get to Mordor and see the Dark Tower? Book Three. Neo beat Agent Smith – a minion—in The Matrix. He didn’t meet The Matrix itself until the third installment. C.S. Lewis had his “last battle”… last. So Lucas is lying. If the Star Wars movies had been intended as a six-part movie series, then the Death Star is in episode six, not four. And Lucas proves my point that the Death Star is supposed to be the high point, the big finish, because he brought it back for episode six, didn’t he? There it was, again, all resurrected and supposedly as bad and scary as before, but it wasn’t, really, anymore, because we’d seen it before and knew it could be defeated.

Even without all the stuff about whether it was an epic or a single-shot movie, Star Wars led to my interest in science fiction and moved me from superheroes who were kind of science-fictiony (The Legion of Superheroes) to actual science fiction, which I began devouring as quickly as I could. I read sci-fi throughout grade school and high school, almost to the exclusion of everything else. And I read a lot of science fiction, and a lot of it was very good, from Douglas Adams’ hilarious Hitchhikers’ books to The Integral Trees to Larry Niven’s great books, all too numerous to name.

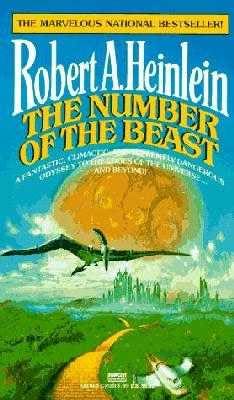

But I didn’t get to The Best Science Fiction writer until I hit college. I was coming home from classes one day, and stopped off at the University Bookstore. It was Friday afternoon, and I wanted a new book for the weekend. (I know, you can’t believe how wild I was, right? Remember, this was when I was still fat and still wore glasses. I didn’t have the eyepatch anymore, but I did smoke, so there you go.) I browsed through the science fiction section and came across a book called “The Number of The Beast” by Robert Heinlein.

It sounded interesting. It talked about other universes and super smart, super sexy people traveling to them. And it started off kind of sexy, too, with a lot of talk about breasts and sex. (I have a theory that if you want someone to just devour your book, put an almost-sex scene into the first 20 pages. From there on out, the reader will be reading in hopes that it will only get hotter. It’s just a theory right now, but watch when my first novel comes out. You’ll see.)

As an aside, Heinlein managed to do that – talk about breasts and sex—in a way that was not at all like porn, and not at all as graphic as some romance novels, but which still seemed more imaginative and romantic and, yes, hotter, than many other writers. That’s part of why he ends up here on TBOE.

But only part. Because even beyond the sex stuff, Heinlein’s book was phenomenal and baffling and wondrous. The general plot was fairly basic - -a group of four people – a dad, his daughter, the dad’s new wife, and the daughter’s new husband – are on the run because someone’s trying to kill the dad, who’s something of an absentminded scientist and who invented a machine that lets you travel between various parallel universes. And, in fact, as science fiction went, it even lacked some things – it didn’t have much in the way of space battles or blasters or the like.

But what it did have was intelligent characters, interesting science that I couldn’t decide was real or not, it seemed real but also too fantastic to be true (the way Ringworld did), a bevy of worlds and commentary on our world and those worlds, trips into literary universes, smatterings of sex, talking computers, and more. The four get into debates on everything from sex to politics to fantasy to leadership, while visiting worlds they’d read about and ultimately finding out the true secret of the universes.

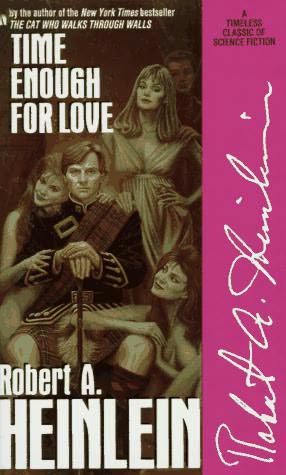

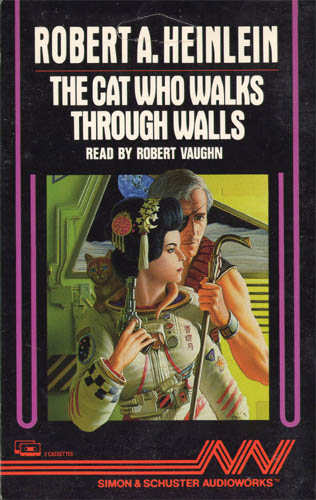

It’s tough to describe just how addictive the book is. I didn’t put it down and read it in just a few days. After that, I was hooked. I went on to other Heinlein books – Time Enough For Love, The Cat Who Walks Through Walls, all of them more or less relating to the same themes and introducing the same characters back and forth and the same kinds of ideas, but always with the kind of witty banter and open attitudes that I envied, and always in worlds that were fascinating – rejuvenation, time travel, moon colonies where they had to pay for air, dead-stick landings of escape pods while dressed as a Shriner carrying a bonsai tree (want to have that last one explained? Read The Cat Who Walks Through Walls).

I instantly loved Heinlein and couldn’t read enough. And then I got to Stranger in a Strange Land, which, oddly enough given how his other books had hooked me from the start, initially put me off. It was the last of his books I read, and it didn’t have any of the characters I’d grown to like except Jubal Harshaw, who I imagined was actually Heinlein injecting himself into the story (and it’s amazing that I can remember these details, because it’s been seven or eight years since I read any Heinlein book at all), but I kept reading because I respected Heinlein, and slowly Mike – Valentine Michael Smith—grew on me, and I grew more and more hooked as he went out into the world and then started a religion,

SPOILER ALERT

and then was killed (I choked up a little but I didn’t cry. Only one book has ever made me cry.) And then it had that strange ending that stuck with me and unsettled me and still kind of does, popping into my head at odd moments.

And that, really, was the heart of Heinlein’s writing. Yes, the science seemed real and still fantastic (read The Menace From Earth and think whether the flying really would be an activity on the moon. It sure seems like it would.) Yes, the characters were interesting and fun and eloquent and debonair. Yes, there were neat inventions (computers with personality, rolling wheels with guns on the moon). But really, the merits of the books went beyond that.

It was the ideas that he put across with his stories, the themes that he presented, that stuck with you.

Themes about the ultimate nature of reality and the stories that we write: Heinlein talked about how all fictional stories are real in some universe, and how the heroes that we create have to have a villain, too, or they feel useless, a theory that applies to regular people and the realities we imagine we inhabit, and our need for conflict to mar the perfection we might otherwise inhabit.

Themes about what it means to be a human: Mike, the martian human, felt that to be human we had to be able to laugh, and that all humor derived from pain and hurting someone, finally explaining that if you examine any funny joke that it involves some level of pain or suffering to someone. (And I haven’t found one yet that doesn’t.)

Heinlein pondered love when he had Richard talk about how he’d do it all again as he

SPOILER ALERT

lay dying on the lunar base trying to save a computer that could coordinate all the universes. He considered what it meant to be family when Lazarus Long traveled back in time to meet himself and his mother in the early 20th century. He created not just worlds, not just a universe, but a whole system of universes and thoughts and characters that did not just inhabit a creation, they breathed life into it. And he did it all with a conversational, fast-paced, witty writing that was more like a friend re-telling you a story that you’d lived through but the friend tells it better than it really was.

I was terribly sad when I found out that Robert Heinlein was dead and would not be writing any more books. I went back and re-read them all again, when I found that out (and I’m inclined to do it now.) I’d torn through his books in a matter of months and then for a while I felt I had no new books to look forward to.

But I did have other books to look forward to, and here’s where mom ended up being so wrong. In his books Heinlein did more than just entertain and teach me. He opened up my mind, and I moved on from reading his books to reading other books and other topics. So his science fiction carried me into his worlds and then back into mine, and opened my horizons up to all the various inventions that writers can create.

Thanks, Robert Heinlein. If you were right about the universe and science, you’re still out there somewhere, but no matter what reality turns out to be, you are and will remain The Best Science Fiction Writer.

No comments:

Post a Comment