Part 3 of my Pulitzer-prize mentioning investigation into what makes a good, or bad, book. Part 1 is here, part 2 is here.

Today: Do you have to call a novel "a novel?"

Author/Secret Agent Patrick Dilloway, who prompted this investigation by posting what he said might be the worst story ever, has written thirty-one different books, by my count. His latest (or latest that I know of) is called Back To Life, and I am in the (very slow) process of reading and reviewing it, but I keep getting sidetracked from that process by (D) Other stuff and (2.7) the fact that every time I start to read it get caught up in the question of what makes a book truly good or truly bad and so I start to deconstruct books and this time the question on my mind is what I started the post with: why call a novel "a novel?"

I started thinking this because I am putting the finishing touches on my own next book -- details soon -- and when I started writing that one, four years ago (!), I put the words "a novel" after the title.

I didn't at the time know why I did that, but I do now, after thinking about it and investigating what it means.

I didn't know what I meant by that at first because as I look back now, the words "a novel" didn't need to be there. I mean, the book is a work of fiction. When published, it will sit on the (virtual) fiction shelf, it will be tagged as fiction, and, when read, as I've no doubt it will be by millions of people, it will be seen as fiction, clearly, or I expect it will because in it William Howard Taft tries to convince a housewife to help expel everyone from Heaven, which is not something I've heard happened in real life.

So because I didn't know why it was there, before setting this book up to publish I deleted that little phrase, "a novel," and went on with my life, but it got me wondering: why bother saying on the cover what it is?

Only books seem to do that, when I started to think about it. You never see "Star Wars, Episode I: The Phantom Menace, A Film" or the like. U2 never released "The Joshua Tree: A Sound Recording." Picasso, so far as I know, never made "Blue Dog: A Painting."

True, movies sometimes say "A True Story" or "Based on a true story," a tagline that automatically irritates me ever since I saw The Strangers, which was a great movie about a brutal home invasion said to be "Inspired by true events," only the true events that inspired this movie were simply "a guy knocked on the director's door once and then left."

The director rejected "Girl Scout Cookies: The Movie"

Seriously: That's what happened, and he used that guy as the inspiration for what was ... was... one of the more chilling movies I'd ever seen, a movie that got that extra fillip of scary because of the thought that some of it had happened, only none of it had happened and if people got a refund for having bought that James Frey book because it was supposed to be true but wasn't, then I'm owed $2 for The Strangers.

So: Calling a book "a novel" seems to have no real point, given that while when you look at a book in isolation, it's not immediately apparent whether you're looking at a novel or a memoir or a cookbook, books aren't in isolation, they're in sections, and also, when you look at a book, while you almost certainly make a great many judgments about that book based exclusively on the cover thereby belying that old saying about books and their covers, I don't know anyone who only reads the title and then buys the book.

Everyone I know who shops for books does this, either in real life or the virtual equivalent:

(17.) They see a cover of a book they like.

(17.) They pick it up and look at the back cover (or page down and read the description, online).

(C.) They shrug and go looking for something that promises to have more sex scenes in it.

(That is why Dilloway's Back To Life, despite not having "a novel" in the title, still has marketing genius behind it; to get to the book online, you have to agree that you're over 18 because the book apparently has so many NSFW scenes in it.)

(The necessity of an early sex scene in a book is one that should be obvious: A great many terrible books-- there was a book I read once about a Tom Cruise-like star in a haunted mansion or something in Hollywood that met this criteria-- have been read all the way through because despite the fact that they were not very good books, they had a sex scene early enough that readers [not just me, necessarily but probably other people] slogged through them in hopes that at least there would be another sex scene to break up the tedium. That's why the Internet will kill reading; people used to go on reading terrible books in hopes of getting to another sex scene. When you're reading online or on a tablet, you're never more than two clicks away from porn and can give up on a terrible book faster.)

In other words, nobody says "I'm going to only read the words on the cover, and I am only interested in books that are clearly novels," so from a marketing standpoint, the words "a novel" appearing on a cover of a book appear to be completely unnecessary.

Or are they?

Does the word novel mean anything anymore? Or is it a code that is meant to appeal to a certain kind of book buyer... let's call them snobs, the kind of people who say things like "Oh, I don't really watch TV" and who eat things that originated (they think) in Eastern Europe but which are actually from a factory in North Carolina.

Here's an interesting fact, if by "interesting" you understand I mean "probably not very interesting to anyone but me": the word "novel" wasn't used to describe a book at all until the 18th century, which is clearly an error on the part of this website that I used as my source for any actual information in this post, because everything was invented in the 16th century, but let's go with it.

The idea of a novel, that site says, came from the Italian word novella, and was used to distinguish a new sort of story from the old sort of stories that humans had been telling until that point. Novels back then were primarily character-driven, 50,000+ word stories. Or, as that site puts it more academically:

The novel places more emphasis on character, especially one well-rounded character, than on plot.

Another initial major characteristic of the novel is realism--a full and authentic report of human life.

The traditional novel has:

-- a unified and plausible plot structure

-- sharply individualized and believable characters

-- a pervasive illusion of reality

Here is another "interesting" fact: Some people are paid to research things like this and do that for a living which is kind of proof, I think, too, that we have more than enough money to do things like "provide free health care to anyone and everyone" because when you live in a society where you can pay people to research novels and other people will pay to learn about that research because those other people want to go on to make their living thinking about novels you are talking about a society that has a serious amount of leisure time and leisure money, so let's get with it people, and start having the kind of country where poor people don't die in the street while we squabble about whether Mitt Romney likes to fire people. (He does.)

I don't just point out that studying novels makes our society "capable of providing health care and education" and "stopping being selfish and stupid" because I'm a jerk. (I am.) I also bring it up because novels are a sign that society is progressing: in the 18th century when novels were not actually invented because everything was invented in the 16th century, the growing middle class was (again according to that site) demanding more literature, which is funny because now we have a shrinking middle class which is demanding more Jersey Shore, although as I look at that sentence nothing is funny about it at all, so I'll move on.

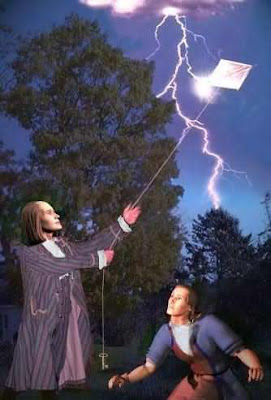

They did some pretty

weird stuff in the 16th Century.

weird stuff in the 16th Century.

While people back then had "literature" such as autobiographies and memoirs (which for some reason people think are two different things) and biographies and romances -- romances being not Fabio-covered women swooning books but grand adventures -- and allegories, people wanted something more real, more lifelike, and so the novel was invented; according to most sources,the "first" novel ever written in English was "Le Morte d'Arthur" in 1470, which is clearly wrong on so many levels that we can go back to ignoring most sources: "Le Morte d'Arthur' is, for one thing, a collection of short stories, so it's not a novel at all and people are ninnies.

Answerbag ("Where the answers are submitted by the same people who didn't know stuff in the first place!") says Cervantes Don Quixote de La Mancha was the first "novel" as we think of it, and actually cites to something that's not Wikipedia, but that site I've been relying on says it's actually Samuel Richardson who "created the novel of character" by writing "Pamela, or Virtue Rewarded" which is a novel told through letters, sometimes called an "epistolary novel" but more often called "an annoying literary device" which didn't get any better when Nicholson Baker transformed it into the all-conversation erotic story Vox in the 20th century, although you can clearly see the trend of novels from that transformation: virtue rewarded to phone sex describes the path of all civilization (hence: Jersey Shore)

Not that the 21st Century is much better,

weird-stuff-doing-wise.

weird-stuff-doing-wise.

But then, too, that site I've been relying on goes on immediately to say that Henry Fielding wrote the first novel, so let's just say "Benjamin Franklin wrote the first novel" because in the United States, that's how we solve everything: attribute it to Benjamin Franklin, a fictional character if ever there was one because by now, to achieve everything Ben Franklin was to have achieved he'd have had to live 300 years and be four people, which he could clearly only do if he'd discovered the Fountain of Youth and used his vast lifespan to acquire huge amounts of wealth and build a mountaintop laboratory in the Appalachians where he discovered cloning and sent out an army of Ben Franklins to alter history from time to time, and I've just plotted out, I realize, the sequel to my previous historical novel ("John Tyler: Space President"). I'll call it "Ben Franklin: Science Warrior". Look out, George R.R. Martin, here I come with the next phase of gritty, realistic, Lord Of The Rings ripoffs.

Add a dwarf, and HBO will

be calling me in 15 minutes.

be calling me in 15 minutes.

I'm getting bored with the history, as I always do. Let's fast-forward:

After novels were invented by Ben Franklin, Science Warrior, they went through a couple of phases that can be described as "18th Century: Bronte-izing the Novel and Making It Boring", with a side trip into "Charles Dickens Writes The Only Christmas Story Anyone Will Ever Hear Again" to the 20th Century Novel, which that site that I've been relying on describes as "we can't really say anything about it" (seriously) (so now people are getting paid to not be able to talk about the thing they get paid to study, so, honestly, I should be able to get a free kidney transplant) to "The Postmodern Novel", 'postmodern' being a term only academics use because "modern" means "relating to recent times" and you can't postmodern is therefore a moving target, but that site that I'm no longer relying on says that the characteristics of the postmodern novel include:

playfulness with language

experimentation in the form of the novel

less reliance on traditional narrative form

less reliance on traditional character development

experimentation with point of view

experimentation with the way time is conveyed in the novel

mixture of "high art" and popular culture

interest in metafiction, that is, fiction about the nature of fiction

Which, if you look at it closely, means that the characteristics of a postmodern novel are that it is not at all a novel.

If, that is, novels mean "character studies that are fictional but which are meant to seem very realistic" which is what I gathered a novel was (because that was what people said it was.)

So, we're back to this:

A novel is a lengthy character study meant to be highly realistic and depend more on development of character than action-driven plots, unless a novel isn't any of those things at all.

Awesome.

So why do people still put a novel on their cover? I think it has nothing to do with making sure you, the reader/buyer (as I've pointed out, book publishers are far more interested in buyers than they are readers) know that a particular book is a character-driven realistic story (unless it isn't), and more in appealing to a certain class of reader: snobs.

I say that because the other history of the novel begins with one of the single-most overrated figures of the 20th century, ranking right up there in overratedness with Kurt Cobain: Andy Warhol.

Pictured: The Death of Culture.

Andy Warhol wrote a book. He called it "a, A Novel." It was not a novel. It was, according to Wikipedia which is fine for dreck like this, a word-for-word transcription of tapes Warhol made with Ondine, and I'm so uninterested in Warholesque Boomer Art that I'm not going to look her/him/it up.

Warhol talked with Ondine for two years (presumably, not straight through, but you never know) and then transcribed it as "a, A Novel" and it got published because publishers even then were trying to kill off reading.

"a, A Novel" is not at all pretentious *where is that sarcasm emoticon when I need it?* in that ... and I'm going to quote Wikipedia directly for the full impact... it is:

Warhol's knowing response to James Joyce's Ulysses [and] was intended as an uninterrupted twenty-four hours in the life of Ondine, an actor who was famous mostly as a Factory fixture, Warhol film Superstar and devoted amphetamine user

That is to say: She was famous for being around Warhol, who was famous for being around people like her. Also: "knowing response to James Joyce's Ulysses"? I've never read Ulysses and don't intend to because I was already burned when people said to read David Foster Wallace's unreadable garbage, but I do know that it's not worthy of a response.

Wikipedia goes on:

A taped conversation between Warhol and Ondine, the book was actually recorded over a few separate days, during a two-year period. The book is a verbatim printing of the typed manuscripts and contains every typo, abbreviation and inconsistency that the typists produced. Ondine's monologues and disjointed conversations are further fragmented by Warhol's insistence on maintaining a purity of the transcriptions.Yes, that is the excuse I use when what I turn out is terrible: "I did it on purpose because doing things badly opens doors," something that's apparently only true for Tim Tebow. Who knew that "hiring bad stenographers and then hanging around drug addicts" would get a publishing deal?

a, A Novel was the second of several publishing projects Andy Warhol produced in his lifetime. ...Warhol wanted to write a "bad" novel, "because doing something the wrong way always opens doors."

Wikipedia has more:

Four typists were employed to transcribe the Warhol/Ondine tapes. Maureen Tucker, the drummer for the Velvet Underground was an expert typist.

Emphatically, she was not, unless the previous paragraph about errors was completely wrong, which, maybe it was, if it was entered into Wikipedia by Maureen Tucker.

However, she refused to transcribe the swear words and left them out. Two high school girls were hired to work on some of the tapes. When one girl's mother heard what they were listening to she threw out the tape, losing several hours of conversation. All four hired typists transcribed the dialogue differently, some identifying the speakers, others not. The editor for a, A Novel, Billy Name, preserved the transcripts as is, with every typo and inconsistent character identification, and even moving from two column pages to single-column based on each typist's style. The final printed version was identical to the typed manuscripts

Sounds hellish, doesn't it? It gets worse:

In his glossary for the 1998 edition of a, A Novel, Victor Bockris cites Billy Name as the source for the title; "a" refers to both amphetamine use and as an homage to e.e. cummings.The title in both editions published by Grove Press in 1969 and 1998 use the a, A Novel format.

Excuse me? "An homage to e e cummings"? Which, I'll note, Wikipedia misspelled as cummings did not use punctuation in his name. (Unless he did?)

Enough. Warhol was beloved by Baby Boomers, which was enough to make him famous and to permanently warp history, the Boomers warping culture the way gravity warps space-time, and by calling "a" "a novel," Warhol, my thesis is, stamped with cultural approval the words "a novel", marking that phrase with a certain kind of cache that is meant to convey, to the buyer -- people who are swayed by the words a novel on a book cover are far more likely to be book buyers than book readers -- that the book on which the words a novel appears is in the same category of things like "documentaries mostly containing subtitles," "Saabs", "things that make me think of lower Manhattan," and "wine country", the message being: "This book will convey to your friends and associates that you are cultured and intellectual."

Lest you think I am too hard on authors who use "a novel" (because I was going to), consider this: I was going to because that particular a novel I thought had a higher literary significance than the other stuff I've written, which is not a hard mark to achieve to do when you consider that "some of the other stuff I've written" includes "a story premised on a joke about Godzilla and Jesus," but the point is that I was trying to be pretentious when I typed that (and trying not to be when I deleted it), and lest you think I am overstating the impact of putting the words a novel on the cover, consider "the Prius Effect."

The "Prius Effect" is an actual thing: It refers to the oddly-shaped Prius car, and the fact that the Prius was oddly-shaped to emphasize that it was a hybrid, which, in turn, made people who wanted to buy hybrids more likely to buy a Prius, not because they were better cars but because they were immediately recognized as green: by buying a hybrid car, you are helping the environment, but by buying a Prius, you are helping the environment and telling everyone that you are helping the environment, the latter being very important to almost everyone who wants to buy a Prius.

The "Prius Effect" means that some people put solar panels in less-than-optimal spots because it's more important to them that everyone knows they have them than that they work, and in terms of a novel means that by slapping a novel onto the cover of your book, you will ensure that potential buyers, and even some readers, of your a novel will be able to advertise to people that they are buying (and maybe even reading) a novel.

That is, when they sit in Starbucks "reading" their new book, people who look at the book will know instantly that the buyer did not buy some trashy romance or boring nonfiction book: the buyer is a serious person who is reading something that hearkens back to literary answers to James Joyce and etc. etc. something art.

In that sense, the words "a novel" are simply, now, a marketing tool, similar to putting "from Steven Spielberg" on a movie poster or "Whole grain" on a box of food: it's a meaningless code phrase meant to convey a certain association to people who don't really care about the contents but who do care about what other people think about the contents.

4 comments:

I saw this book on the Amazon Vine newsletter last month called "Taft 2012" And guess what, it says "A Novel" on it.

http://www.amazon.com/gp/product/1594745501

If you think Warhol's writing was bad you should try reading Dali. As with most of Warhol's work, and POP art in general, the idea is more important than the product. I didn't see much of a connection with Arcimboldo's fabulous portrait of Rudolf II but it's always fun to see.

Maybe I'll change the name of my book to The Novel on the Corner: a House. Or : a Novel.

Hmmm...

To go with the double redundant or not?

BTW, I noticed this morning my cover for "Where You Belong" has "A Novel" on it. I'm just pretentious that way.

Post a Comment